In 1881 the Chiricahuas of the Apache nation raided the frontier settlement of Cubero, New Mexico, taking a local woman hostage. In time, Plácida Romero was able to return to Cubero and the ordeal inspired an “Indita” or frontier balada recounting her experience in the former Spanish colony. To this day, the descendants of Plácida sing her balada. The “Indita” was a story-telling genre used to record and communicate significant events of everyday people in the United States Southwest. This type of cultural export into the Americas was common in the Spanish colonies. It came alongside smallpox, measles, and typhus with the first conquistadores as part of the “Romancero” tradition. The late medieval troubadour tradition of creating lofty verses in the Iberian Peninsula eventually lent itself to the task of recording localized events in the American colonies. Today, the genre can be traced to corridos and Banda music in México, vallenato in Colombia, and décima and guajira in the Caribbean. It is by virtue of this genre that we get the story of the outlaw Joaquín Murieta fighting the XIX century California land-grab movement by “American” settlers, or the XXI century corridos that tell stories of border dynamics, emigration, drug lords, and the unfulfilled American dream.

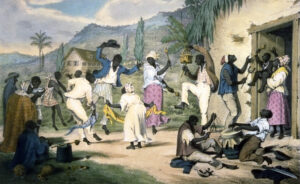

As a companion practice, we must recognize the many indigenous groups in the Americas that used music and dance as the means to communicate stories across generations. We can offer as evidence one of the few surviving Mayan codices, the Popol Vuh, as a record of oral history created in dance and music, as well as the many still surviving “story songs” of the indigenous populations of the hemisphere. There is a lesser-known Old World cultural export to the former Spanish colonies that is equally important in telling stories of resistance, resiliency, and forewarning: African slave rhythms.

In his new album Debí tirar más fotos – DtMF (I should’ve taken more pictures), Benito Antonio Martínez Ocasio, alias Bad Bunny, brings to the forefront these traditions. At the core of this 17-track album, alongside the expected reggaeton, dembow, drap, and hip-hop, is a revival of Afro-Puerto Rican and criollo-Puerto Rican rhythms. The zeitgeist of the collection goes back to the fundamental elements of the African slave rhythms, the Taíno guasábara and the balada: to recount a vital story that warns the population of impending danger. The song “Lo que le pasó a Hawaii” (“What happened to Hawaii”) headlines the “call to arms” and makes use of a slowed down, almost to the cadence of a prayer, “plena” rhythm to condense the sentiment: “Quieren quitarme el río / Y también la playa / quieren al barrio mío / y que tus hijos se vayan” (“They want to take our rivers, also the beach, they want our neighborhoods, and for your sons and daughters to leave”). The ubiquitous question is: who represents “they” and therefore, who are “we” in this Straussean equation?

The answer is to be found in the intricate, complicated, and often maligned island relation to the colonial policies imposed from the mainland and reflected in the album. There is an intentionality, a maturity of ideas, in this collection that we have not seen before from the globally most streamed artist for three years (2020 – 2022). In the title track “DtMF”, the artist lays the task ahead, saying “Ya no estamos pa’ la movie y las cadenas / Estamos pa’ las cosas que valgan la pena” (“We’re not about going to the movies and wearing keychains / Now is about the things that really matter”). What follows is a collection that brings to the vanguard the fear of cultural erosion and displacement inherent in the influx of capital and unbalanced policies that favor foreign intervention in island affairs.

The album is not without controversy. In Puerto Rico, the older generations question why it should be Bad Bunny, known for his racy and graphic lyrics of previous albums, the artist entrusted with representing the traditional rhythms when other artists who have dedicated their lives to preserving such traditions go unnoticed.  For the younger generations on the other hand, he is the perfect example of the evolution of an identity that no matter how progressive, bombarded by “American” ideals, and besieged by massive migration to the mainland, remains fundamentally and proudly Afro-Latin American in its identity. Regardless, the ideological scope of the album can’t be ignored by both camps, and it has already reverberated across Latin America, with over 35 million streams in the first 24 hours.

For the younger generations on the other hand, he is the perfect example of the evolution of an identity that no matter how progressive, bombarded by “American” ideals, and besieged by massive migration to the mainland, remains fundamentally and proudly Afro-Latin American in its identity. Regardless, the ideological scope of the album can’t be ignored by both camps, and it has already reverberated across Latin America, with over 35 million streams in the first 24 hours.

The prelude to the collection is a short film produced by Bad Bunny bearing the same title as the album. It tells the story of Benito as an old man, meandering through his town on an island overtaken by signs of U.S. acculturation and displacement. The imaginary companion of old Benito, Concho (inspired by the endangered Puerto Rican toad peltophryne lemur, not the well-known national symbol of the coquí frog), reflects a state of dementia or perhaps a collective unconsciousness that is “innocent” of the changing cultural landscape around them.  Concho listens in as the old man quips that things have changed so much that now the local “panadería” serves “quesito sin quesito” (traditional cheese puff pastry without cheese). Almost as if saying “you can’t call it Puerto Rico without any Puertoricanness in it”. Indeed, this is not the Puerto Rico of his younger years, where locals would cruise the neighborhood in their “jipetas” blasting reggaeton through the same streets that English is spoken in future-Puerto Rico. The time to avert this possibility is now…or so goes the message.

Concho listens in as the old man quips that things have changed so much that now the local “panadería” serves “quesito sin quesito” (traditional cheese puff pastry without cheese). Almost as if saying “you can’t call it Puerto Rico without any Puertoricanness in it”. Indeed, this is not the Puerto Rico of his younger years, where locals would cruise the neighborhood in their “jipetas” blasting reggaeton through the same streets that English is spoken in future-Puerto Rico. The time to avert this possibility is now…or so goes the message.

As it turns out, the message echoes the experience of inhabitants from around the world. In the streaming platform Youtube, where the short film debuted, comments range from “Si te hace llorar y eres ajeno a PR es porque dentro de tu pecho late un corazón latinomaricano” (“If it makes you cry and you’re not from PR it is because your heart is Latinamerican”; @aliciamieses9012), to “This film deserves an award. It gets to the heart of ‘globalization’ and the vanishing of cultures” (@sylvial8411), to “I’m from France and I’ve cried on it, I’ve spent all of my evening searching about Puerto Rico and its history” (@Louise007), to “Soy the Brasil y me hizo llorar! Que viva la Resistencia de la cultura latinoamericana” (“I’m from Brasil and it made me cry! Long live Latinamerican cultural resistance”; @victoriaalbuquerque982).

The conceptual response of the album to the threat of cultural erasure is a grassroots return to the very rhythms that created the island’s musical identities. They arose as points of resistance in the island’s cultural milieu over the centuries and have at their core the same story-telling purpose that assailed cultures have used in the Americas and West Africa to resist, warn, call to action, and survive. To this purpose, the album showcases and blends salsa, jíbaro, plena, bomba, a dash of bachata in the song “Bokete” and more than a hint of “trio” bolero in “Turista”.

Bomba is one of the oldest Afro-Puerto Rican rhythms, associated with the early slave settlements and their need to bring together a diverse West African population on the island. It is intimately associated with the town of Loiza, on the northern coast of the U.S. colony, and it fuses percussion drums with a pre-columbian Taíno (indigenous population of the island) instruments like the “güiro” and “maraca” (themselves two of a handful of Taíno words that the conquistadores spread through the Americas and into the English language: others being huracán, barbacoa-BBQ and canoa). Plena is associated with the southern semi-arid belt of the island. Emanating from the town of San Antón, Ponce, in the late XIX to early XX century, as a form of recording and passing along meaningful stories among the slave and “freemen” populations. It lingered long enough to be picked up in the second part of the XX century as the rhythm of choice for political and social discord on the island. Today, its resurgence as popular music is only matched by its potential to bring people together in protest.  Early forms of the rhythm such as “Tintorera del mar” (1954) with its catchy refrain “Titnorera del mar…que se ha comido a un americano” (“Female shark…that has eaten an American”), “Mataron a Elena”, about an early account of femicide, and “Santa María” (“Blessed Mary”) and its prayer for the population to be delivered from the attack of a demon (in later versions the demon can be found to be a hurricane), are early versions of the potential of the rhythm to record and transmit urgency to the population.

Early forms of the rhythm such as “Tintorera del mar” (1954) with its catchy refrain “Titnorera del mar…que se ha comido a un americano” (“Female shark…that has eaten an American”), “Mataron a Elena”, about an early account of femicide, and “Santa María” (“Blessed Mary”) and its prayer for the population to be delivered from the attack of a demon (in later versions the demon can be found to be a hurricane), are early versions of the potential of the rhythm to record and transmit urgency to the population.

Although the album is not without precedent —indeed there is a long tradition of using music as protest on the island, including Ruben Blades and Willie Colón’s seminal salsa album Canciones del solar de los aburridos with its track “Tiburón” speaking of the U.S. Army land grab in Vieques—, there is in Benito’s version an intention to conceive of Puerto Rico as an imaginary. Its borders are not only geographical but include the collective experience of the diasporic island. In the track “DtMF” as the voice rejoices in watching a sunset in Old San Juan, it brings into dialogue the more than 6 million Puerto Ricans living in the United States when it reflects on its own condition as someone who is “disfrutando de todas esas cosas que extrañan los que se van” (“enjoying all of the things that are missed by those that leave the island”).

Drap turns into plena precisely when the call to arms, the waring, the impending message is needed; much as the Taínos did to defend their lands, much as the West Africans did when made slaves or their colonial descendants did when their barrios and culture got cornered by the dominant culture in the island. At this precise moment the song moves from the single voice of Bad Bunny to the communal “plena” choir of “all of us” in chanting “Debí tirar más fotos de cuando te tuve / Debí darte más besos y abrazos las veces que pude / Ojalá que los míos nunca se muden” (“I should’ve taken more pictures when I was with you / I should’ve kissed you and hugged you more the times I had the opportunity / I hope mine never have to move”: mine = my people). The song goes back and forth between the personal (love lost) and the collective (island that can be lost). Puerto Rico is the object of desire, of nostalgia, it is the one loss the islanders can’t afford to materialize, and it is through the device of recording what is loved that one can truly gaze at what could be lost in the future. The refrain has become a common viral trend in social media where it’s used to curate scenes from the island’s beautiful landscapes or pastiches of loved ones that have passed away.

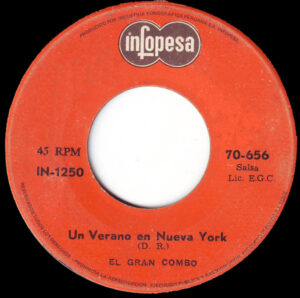

Puerto Rico is at once the island, the diaspora, and the multitude of people around the globe facing cultural erasure. The capitalist push of a new form of American Manifest Destiny are the agents of forced culture-building. Salsa, a Bronx-Puerto Rican phenomena inspired by Cuban son montuno takes center stage in “Baile inolvidable” where the voice laments that “Pensaba que contigo iba a envejecer / En otra vida, en otro mundo podrá ser / En esta solo queda irme un día” (I thought I would grow old with you / Maybe in another live, another world / In this one I will have to leave”) is a play, we suggest, not just on the idea of a lost relationship but also a lost homeland, much like in the song “En mi Viejo San Juan”, a much older and beloved lament of the distant diaspora. Salsa is a fusion, African drums, Taíno clave, güiro and maraca, and European horns, and as it exploded from the Bronx to the island, and from the island to Latin America and the world in the late ‘60s, it also established the indelible truth that Puerto Rican identity extends beyond the island. It returns in the track “Nuevayol” as a tribute to the 1975 hit by “la Universidad de la salsa” group El Gran Combo “Un verano en Nueva York”.  The song takes salsa almost to the Bomba territory, to repeat the Grand Combo invitation to visit NY for a fun summer (“un ratito na’ ma’: for a bit only”), but this time, not just the Bronx, but also to visit the Heights (Dominican Enclave), enjoy Willie Colon’s music (the OG of Bronx salsa), sell counterfeits music, and drink “cañita” (sugar cane moonshine) on the stoops.

The song takes salsa almost to the Bomba territory, to repeat the Grand Combo invitation to visit NY for a fun summer (“un ratito na’ ma’: for a bit only”), but this time, not just the Bronx, but also to visit the Heights (Dominican Enclave), enjoy Willie Colon’s music (the OG of Bronx salsa), sell counterfeits music, and drink “cañita” (sugar cane moonshine) on the stoops.

The trope of the island as a fusion of many cultures and a product of the plantation system, particularly after 1821 and the collapse of the Spanish empire, can be seen in the album’s reference to many ways rum binds together African, Indigenous, and European cultures. It is the elixir of choice for fun, celebration, and lament. It is central to the track “Pitorro de coco” (Coconut Moonshine) and the traditional rhythm it uses: jíbaro music. Jíbaro music arose during colonial times, as the “criollo” or colonial subject retreated to the mountains in the island and created its own unique culture based on sustenance agriculture and a simple carefree lifestyle. It angered the Spaniards that the population would adopt a commercially unproductive lifestyle, but it also engendered through “música jíbara” (seis, décima, mapeyé: a fusion of Spanish balada with Taino and African contributions) one of the most enduring lyrical traditions exalting the simple life and love for God and the land. Bad Bunny fully adopts the genre in this track, telling once more the story of love lost, and “otra Navidad que no estás aquí” (“another Christmas without you”). The song is a bold statement and speaks of the ability of the singer to dig out island cultural markers and present them as popular music.

“Café con ron” completes the ensemble of songs to the rum gods. The echoing of the island’s African rhythms of bomba y plena, the homage to salsa music, and the repurposing of “música jíbara” to advance a message of urgency to the uneven shifting and displacement of cultural values is what gives the collection its powerful voice, and this particular song its purpose. From the onset “Café con ron”, a collaboration with the plena ensemble Los Pleneros de la Cresta is a choir of voices. It is the collective voice of the island chanting “Por la mañana café / Por la tarde ron / Ya estamos en la calle / Sal de tu balcón” (“In the morning coffee / Rum in the afternoon / Already on the streets / Come down from your balcony”). The song is a roll call of places on the island, as if making the rounds through them allows the poetic voice to invite its inhabitants to “get out” and have fun. “Enjoy it while it lasts” one can guess.

It is the collective voice of the island chanting “Por la mañana café / Por la tarde ron / Ya estamos en la calle / Sal de tu balcón” (“In the morning coffee / Rum in the afternoon / Already on the streets / Come down from your balcony”). The song is a roll call of places on the island, as if making the rounds through them allows the poetic voice to invite its inhabitants to “get out” and have fun. “Enjoy it while it lasts” one can guess.

There’s plenty of vintage Bad Bunny in this collection; plenty of references to drinking, drugs, female objectification, sex, and love gone bad. But in electing to use Afro-Indigenous-Spanish story-telling genres such as the ones he mentions at the end of “DtMF”, when the poetic voice reminds us Boricuas that now “estamos pa’ la cosas que valgan la pena / Pa’l perrero, la salsa, la bomba y la plena” (“we’re about the things that matter / perreo, salsa, bomba and plena”), there’s a new agency as well. Carlos Vives did it with vallenato, Juan Luis Guerra did it with bachata, and now Benito attempts to bring to the popular sphere the very rhythms born out of resistance, resiliency, and the need to establish a point of defiance.

The message takes laser focus on the track “Lo que le pasó a Hawaii”. The song is a recollection of a bad dream (“Esto fue un sueño que tuve”: This was a dream I had) about “Her / the motherland”. And in it, we first see an nostalgic image of “her” as the voice comments that “Ella se ve bonita aunque a veces le vaya mal / En los ojos una sonrisa aguantándose llorar / La espuma de sus orillas parecieran de champán / Son alcohol pa’ las heridas…porque hay mucho que sanar” (“She looks beautiful even when at times things go bad / In her eyes a smile holding back the tears / The water splashing on the shore looks like champagne / it’s alcohol to heal its many wounds”). It goes on to mention how in the interior of the island one can hear the same “jíbaro” lament of yesterdays complaining about those who already left. It is not an intentional exodus, they never are, rather the result of displacement, imposition, and cultural erasure that arise from decades of colonial policies and the use of the island as a U.S. resort for capitalist agenda. The Afro-Puerto Rican rhythm it uses, as slow down version of jíbaro music empowers, besieges almost, the reader to act: “No sueltes la bandera / No olviden el le lo lai / Que no quiero que hagan contigo / Lo que le pasó a Hawaii” (“Don’t let go of the flag / Don’t forget the le lo lai / I don’t what them to do with you / What they’ve done to Hawaii”). It is a string of subjunctive verbs, the tense used in Spanish to communicate desire and acts that are yet to be determined, and in them, they contain the author’s wish for the island, its diaspora, and the future.

If the island is to survive acculturation and displacement, the song continues, one must understand that just like current migration tendencies into the U.S., “Aquí nadie quiso irse / Y quien se fue sueña con volver” (“Nobody wanted to leave (migrate) / And those that do dream of returning”).  It’s a journey of necessity, the very ones created by failed, rather, ill-intentioned, U.S. decades-long policies, not of choice. As Bad Bunny says to summarize his plight for action and resistance: “Seguimo’ aquí” (We’re still here). Pride engenders unity, from unity resistance germinates, and in showcasing Afro, Taíno, and Spanish story-telling rhythms of the island’s many resistance movements, Bad Bunny takes one step forward towards turning resistance into action. Guasábara! In the tenor of social realignment and personal anxiety over current political discourse, the collection is a noteworthy contribution to the genre of storytelling through music, and a great example of the synergy popular music can have with traditional rhythms. From a Professor of Latin American literature representing the diaspora and a different generation, I shout back by saying “Well done Benito, nosotros también seguimo’ aquí”.

It’s a journey of necessity, the very ones created by failed, rather, ill-intentioned, U.S. decades-long policies, not of choice. As Bad Bunny says to summarize his plight for action and resistance: “Seguimo’ aquí” (We’re still here). Pride engenders unity, from unity resistance germinates, and in showcasing Afro, Taíno, and Spanish story-telling rhythms of the island’s many resistance movements, Bad Bunny takes one step forward towards turning resistance into action. Guasábara! In the tenor of social realignment and personal anxiety over current political discourse, the collection is a noteworthy contribution to the genre of storytelling through music, and a great example of the synergy popular music can have with traditional rhythms. From a Professor of Latin American literature representing the diaspora and a different generation, I shout back by saying “Well done Benito, nosotros también seguimo’ aquí”.