Avid Latina reader gets real about impact of book bans

By Natasha Ford

Book Banning is a hot-button issue right now all across the United States. The communities being targeted most frequently are the LGBTQ+ and Black communities, but the Latinx community is seeing its fair share of banning as well. The book being cited most prominently in Texas for inappropriate content is Out of Darkness by Ashley Hope Perez, with several other books on lists all across Texas. But who gets to decide which books get banned and why? Why are these books being banned? What books get banned and what books stay on the shelves in schools and public libraries?

I’m not going to attempt to answer any of these questions, but what I will say is that censorship and book banning divide communities. Throughout history, not one group of people who decided to censor or ban books has ever been seen as the heroes. The most well-known groups to fall under this category include the Nazis, who killed about 11 million people, and Communist Russia, which overtook countries like Ukraine and Lithuania.

I come from a mixed-race family and am white-passing. My father is white and my late mother was Cuban. When I was really young, before my family moved to Texas, I was surrounded by Cuban culture in Florida. We lived near my grandparents and celebrated our culture by listening to Celia Cruz or Cuban jazz, eating tostones and empanadas, and dancing. When we moved from Florida to Texas, there was a shift. No longer was our culture celebrated outside of our home. We were a white family.

My attempts to share my culture with friends throughout the years were met with disdain, jeers, and judgment. I was too pale-skinned to be accepted by the Latinx community, and too Latinx to be accepted by the white community. So, in order to fit in, I stopped trying to share my Cuban culture and just focused on the white half. I stopped listening to Latinx music and I stopped dancing — the food never went away, but I stopped trying to share it with my peers. Most of my friends didn’t even know I was mixed. It wasn’t until after I graduated college that I accepted my Cuban half again. And you know what brought me back? Books.

All throughout my adolescence, I read books by white authors, writing about white worlds. It was rare to read books by or about people of color or the LGBTQ+ community. It was hard to venture outside the world of whiteness in publishing. It wasn’t until several years ago that the whiteness of publishing was really called out and publishers started making a concentrated effort to diversify their catalogs.

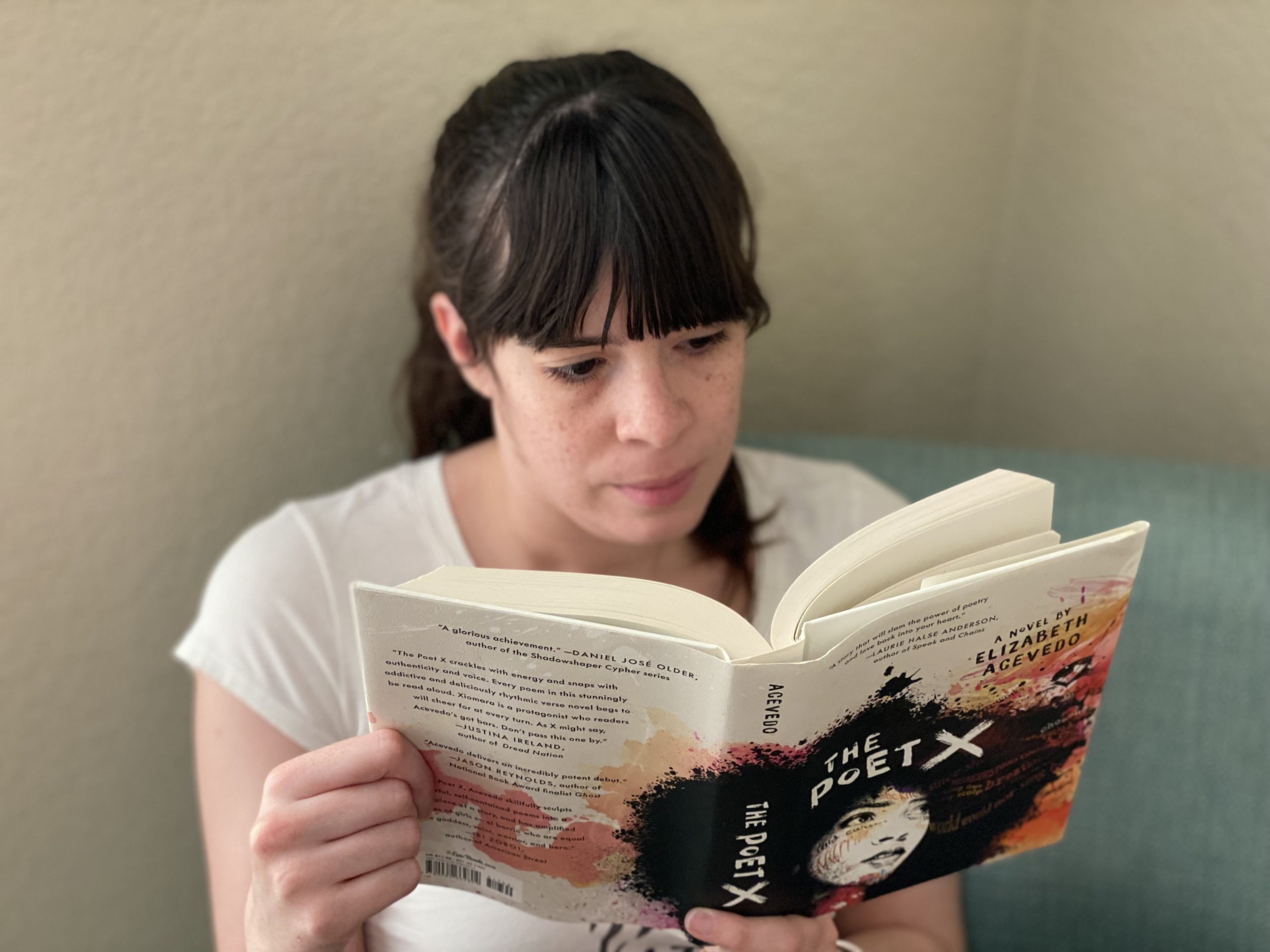

After I started working at a bookstore, I started getting back into children’s books, mostly middle grade chapter books and young adult. I remember when I laid my hands on the first book I had ever seen written by someone Latinx. It was The Poet X by Elizabeth Acevedo. I read it in one sitting, and I cried while reading it. It was like someone healing a wound I didn’t even know I had. The Poet X was unapologetic and beautiful. It made me realize that I didn’t have to hide half of my culture away. I am Cuban and I should embrace that half of me.

I started cooking Cuban dishes, listening to Cuban music, dancing, and reading all of the Latinx books I could get my hands on. Many of these books I have reviewed for this very magazine. I realized that I can be both: white and Latinx. I don’t have to choose. I shouldn’t have to choose. No one should feel like they have to hide parts of themselves away to feel safe or accepted by their peers — or even among strangers. As someone who did that for many years, I can say that it feels horrible. The constant worrying about, when someone finds out you are mixed, if they will treat you differently. Will they still accept who you are, or will there always be that lingering feeling that they don’t love all of you?

My parents never tried to censor what I read, in school or for leisure. They knew if I was confronted with a topic I didn’t understand, I would research it, and if I came across a topic that made me uncomfortable, I would talk about it or stop reading the book. They trusted me to make my own decisions when it came to what content I could handle and what I couldn’t. They never fought with me about what books I could or could not read.

They would often make suggestions or ask what I was reading, but they trusted me to make my own choices. So I read everything I could get my hands on. Reading was often an escape for me. It was a way for me to process the world and make sense of it. Instead of censoring or banning books from schools and public libraries, parents should trust their children to make the right choices for them. If a book or topic interests them, they should be able to explore because it teaches them more about the world and themselves.

Books unite us. They teach us compassion. They heal wounds. They help us learn about ourselves and others. Banning books and censorship is taking away someone’s opportunity to find their community and embrace their true self.

Banning books and censorship is taking away someone’s opportunity to learn something new. It takes away the opportunity to feel safe and loved. The people banning books and screaming about inappropriate content for their children fail to understand this concept. Most of them feel like they are trying to protect their children, but what they’re really doing is hurting them. For so many children and adults across the globe, books are a safe haven. No one group or person should have the right to tell me or anyone what books are appropriate or should be read.

I desperately wish that more books by Latinx authors and about Latinx culture were available to me when I was growing up, and I am happy to see the number of books available for children rising. I’m happy to know that, if I ever have children, books about their culture will be available to them and, maybe, they won’t feel so alone.